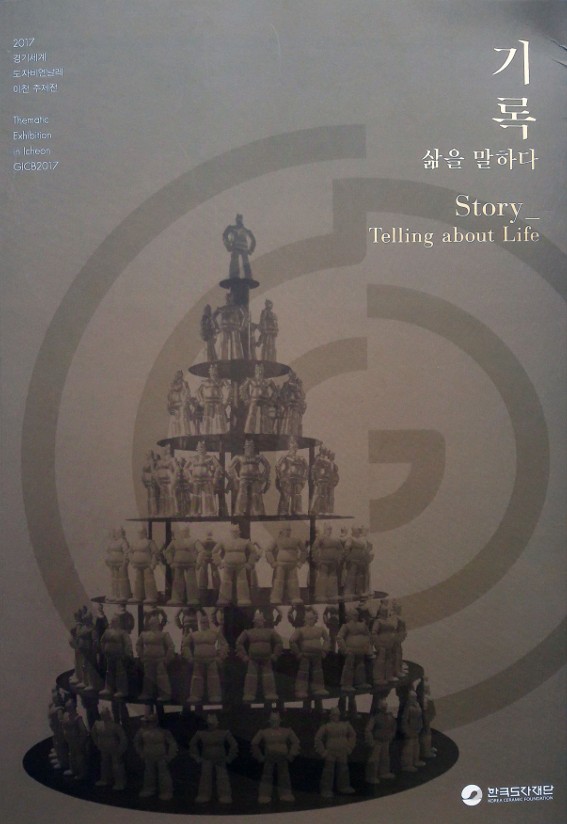

“This German-born ceramic artist has been producing small, clay human figurines that depict images distilled from the artist’s observations of herself and others. By capturing fashion trends as well as individuals in the act of fulfilling their given roles in society, Roos’ figurines effectively reflect the social instincts, significance, and roles of humans as cultural beings, over and beyond mere individuals. Her human figurines are therefore not representations of isolated individuals, but reflections on the modern world, where diverse individuals mingle and coexist together.”

Catalogue from the Gyeonggi International Ceramics Biennale 2017, p.84

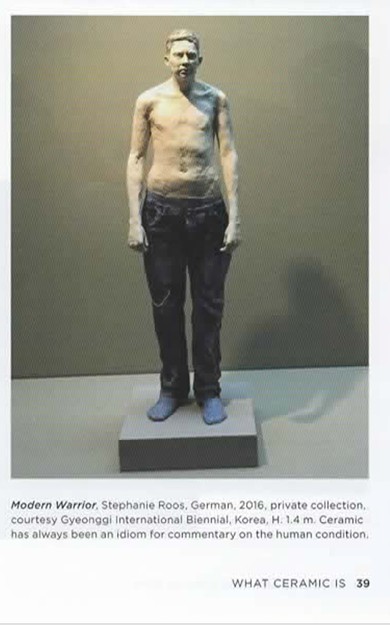

“The main point being made here is to foreground the fundamental role of the human form within the ceramic heritage. We tend to associate the rise of the figurine, and indeed the word itself, with the 18th century, and the European discovery of porcelain. But it is important to remember that it didn’t begin then. When contemporary artists like Viola Frey (1933–2004), Claire Curneen (b. 1968), Stephanie Roos (b. 1971), Philip Eglin (b. 1959), or Michael Flynn (b. 1947) make figures, they tap into something deep, primordial even, about ceramic practice.”

Paul Greenhalgh: “Ceramic Art and Civilisation”, 2021, p.40

“A string of exhibitions and publications over the last two decades, such as Confrontational Clay (2002), Ceramics, Ethics, and Scandal (2002), Sexpots: Exoticism in Ceramics (2003), and Subversive Ceramics (2016), have understood ceramic to be a vehicle for difficult social ideas. ⁸⁶

Paul Greenhalgh: “Ceramic Art and Civilisation”, 2021, p.467

The international scene boasts ever-increasing numbers of artists who want to deal with the world they inhabit. Among the better known are Americans Matt Nolen (b. 1960), Cynthia Consentino, and Janis Mars Wunderlich; Esterio Segura (b. 1970) in Cuba and Bita Fayyazi (b. 1962) in Iran; Bouke de Vries (b. 1960) in the Netherlands, Daniel Kruger, Paloma Varga Weisz (b. 1966) and Stephanie Roos (see page 39) in Germany, and László Fekete (b. 1949) in Hungary. ⁸⁷

All these artists are intensely representational, creating ensembles that edge into the Surreal.”

Magic Reality

In June of last year Stephanie Marie Roos brought us some of her new work. In these life-size busts, she, even more, focuses on details in her excellent technique. Even if these are portraits of someone you might know – my first exclamation when I saw the “Butterfly Man” was “I know him!” – it is not about similarity: These works tell something beyond the image, the figures are ‘talking to you’.

Stephanie described the new approach as a more psychological way to dive into human expressions without having a big gesture, but a magic moment.

“Being deeply immersed in a portrait means so much more than depicting a person.

In addition to capturing the essence of the represented person, it is always a psychological examination of one’s own person and history. It is a kind of exploration of the foreign and the own … what I cannot see in myself allows the image of the other…

Simone Haak and Joke Doedens (Terra Delft Gallery, Netherlands) in “new ceramics”, 02/2021

Sometimes arises a fantastic element, that complements the portrait and connects it with another level beyond individuality and symbolizes the general tragedy of existence – transience, error, fear, desires, loneliness…. ” (S. Roos)

When our exhibition planning became concrete, she told us, that the portraits have been inspired by the book “Killing Commendatore” by Murakami, and her suggestion for the exhibition title “Magic Reality” seemed very well matching with her pieces.

“Killing Commendatore” tells the story of an abstract painter, who earns his living by portrait painting. Since he has a special memory for faces and an eye for the essentials of people, he is good at his business but loses somehow the connection to his actual artistic work. When his wife leaves him, he gets into a life crisis. A confusing journey with strange encounters and surreal elements begins. Among other things, he finds a painting that depicts the murder scene from Don Giovanni. This picture-“Killing Commendatore”-opens a new perspective for the painter and becomes his new artistic guideline.

“I had been carrying around this idea for a long time – to give Murakami’s books a shape. You can say, he is my literary role model. I am fascinated by his clear narrative style, accuracy, the vividly described figures, always with very precise images of their clothes, and at the same time the surreal and the magical moments. I adore his complexity and freedom in the choice of motifs, the ease with which he writes a story, playing in contemporary Japan, and at the same time sends his readers on excursions into world history and uses motifs from art history, mythology, and fairy tales.

That I was already amidst this work and that it wouldn´t be an illustrative work, I realized after a series of portraits. I had embarked on the path of Murakami´s protagonist, the nameless portrait painter. ” (S. Roos)

The painter in the book no longer wants to paint portraits but is given this task again through a lucrative commissioned work. However, this client’s expectations differ from the usual ones, who are simply satisfied with a great similarity. Thus, the artist the first time has the freedom to turn his craft into an artwork, in which the moment when a portrait becomes “universally valid” does not depend on the similarity. In this way, the artist finds his own freedom again and he tries to paint a portrait of a man whose face he cannot forget and who embodies his fears: The Man with the White Subaru Forester. This portrait fails because he is unable to continue this painting.

“Some of my models were randomly chosen people because they found the idea exciting or because they didn’t mind being photographed. I asked for photos because something had appealed to me and I wanted to find out what. Some of them are self-portraits. Sometimes, there was the story first, and then the person. But those where the story emerged while working were magical … There were also many moments of struggle, and portraits that simply refused to emerge as it happens in the book, where the painter is not able to continue with one special painting and he is told: “Leave it alone!” (S. Roos)

Terra Delft has a long history of exhibiting figurative sculptures. After enlarging and reopening the gallery in 2001 we showed works of Carolein Smit, who shooked up the art scene by her controversial subjects. Also, Alessandro Gallo´s half-animal half-humans has been shown in our gallery. Both artists became world-famous and are international well recognized.

We are proud to show Stephanie Marie Roos´s sculptures in Delft and also see a great future for her artworks: Here we see an artist who is a ceramicist in heart and soul, making perfect realistic ceramic sculptures. For a ceramic art gallery as Terra Delft this is a real delight, these works bring together the different aspects of ceramic art; idea – technic – expression.

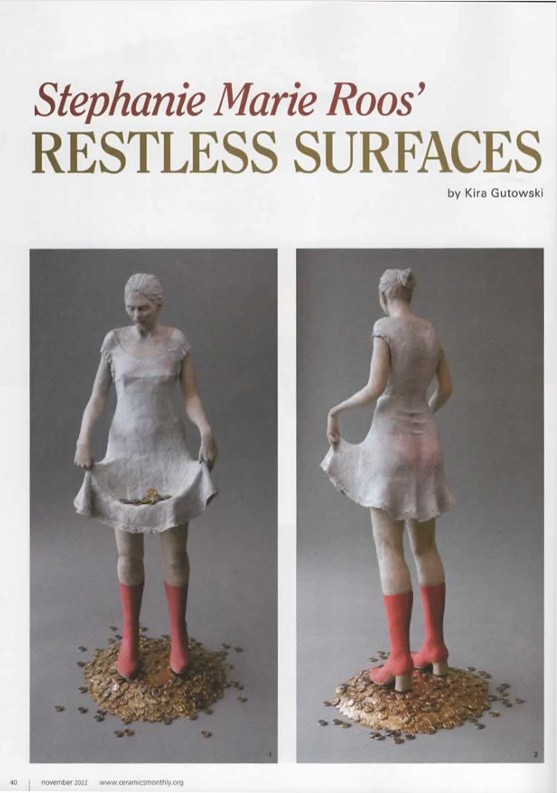

Restless Surfaces

“Like all art, the perception of it goes beyond rational thought and words. Figurative ceramic sculpture, as it is presented by Stephanie Marie Roos speaks primarily to our subconscious and creative mind, our intuition, and our emotions. The works of Stephanie help us explore how we perceive identity and the hidden parts of ourselves which do not find a lot of expression in our modern world.

Stephanie grew up in an innately creative household. Her mother was an arts and crafts teacher, and creative projects were constant companions in her early childhood. At the age of nine, she was thoroughly inspired by local figurative ceramic artist, where she found a love of art and figurative sculpture. A seed of desire was planted, “I adored his work and I wanted to become an artist just like him. That was when my plan was actually set.” But her well-meaning parents encouraged a more sensible career – teaching – which she obediently followed. In addition to teaching art, Stephanie also trained and worked as a graphic designer. However, these paths were not fulfilling in a meaningful way, and her personal creativity and a desire for self-actualisation pushed its way to the surface. Stephanie explored various artistic mediums, but finally the pull towards working with ceramics returned, and she learnt how to wheel-throw, bought a kiln, and set up a studio in her home. Initially it was intended as a hobby, but immediate success and positive feedback combined with the comfortable feeling of working with clay, cemented the idea to forge a way as a professional ceramic artist.

Kira Gutowski in “Ceramics Monthly”, November 2022, p.40-43

Since then, the year was 2012, Stephanie has not looked back. She now diligently works in the studio for around six solid hours each day. This disciplined approach has resulted in a vast amount of work in a short space of time.

The emotive human figure has become synonymous with Stephanie’s personal style, and it provides the perfect platform to express a complex story. Her works are full of poignant imagery that instantly evoke feelings and emotions we can all relate to, without necessarily fully understanding the story that is being told. Her artwork perfectly embodies how we, as humans, grapple with identity, cultural norms and influences, questions about gender, our cognitive dissonance, as well as our intense desire for connection and acceptance. How we play out our personal story on the cultural stage. Each facet of her sculptures symbolizes an aspect of these individual stories.

The exteriors of Stephanie’s sculptures are minimally decorated so the attention is not drawn away from the sculptural form and the materiality. Colour is used sparingly, and specifically. For example, the woman depicted in ‘Woman with Pom Beanie’ (2020) is almost entirely pale with a bright red pom-pom on top of her beanie. From the front, everything appears to be normal, however, viewed from the back, the red pom-pom appears to be bleeding red (blood implied?) down the woman’s back. Or in the work ‘Coincidence’ (2019), the woman is mostly light-coloured except for her red boots and underwear, and the golden coins she holds in her dress and on the ground. Colour is used to bring gravity to an aspect of the sculpture, usually an item which has cultural significance.

The surfaces of Stephanie’s sculptures are deliberately kept imperfect. She lovingly calls them her ‘restless surfaces’. “I like that one leaves traces of oneself in the work. I don’t do smooth. Smooth makes the work lifeless.” The textured exteriors impart a feeling of movement and changeability and help convey the complexity of the inner emotive reality.

Recreating clothing with clay has its own fascination and challenges. The texture of the fabric, the way it falls around the body, and what the body looks like under the fabric, are all aspects that draw Stephanie’s attention. The clothed person also provides an endless source of cultural analysis. Why has it become acceptable for western women to wear pants, but not acceptable for men to wear skirts? How can a hoodie represent danger? What is the significance of a bag? How does our attire separate or connect us? These questions arise through current affairs or themes found in photos or images. If a question holds her interest, Stephanie will do a deep-dive into the subject matter, often going down a rabbit hole of historical and cultural questioning. This curiosity will occasionally lead her to dark places, but her search must go where it must – she is seemingly fearless in that regard.

The piece ‘Protest Icon’ (2021) is particularly poignant, as the last few years have been coloured by many political protests all over the world, including social inequality demonstrations such as ‘Me Too’ and ‘Black Lives Matter’ and environmental activism with ‘Fridays for Future’. ‘Protest Icon’ depicts a teenage boy wearing a jacket with a fur-rimmed hood. The fur is golden, making it reminiscent of a halo depicted in iconography, however, the boy is also wearing a Levi’s t-shirt, possibly indicative of the personal conflict between cultural positioning and the desire for societal change. In addition, his youth and choice of clothing demonstrate the dissonance between the developing adult and the reluctant necessity to request change of the governing adults.

Aside from a physical representation that is very realistic despite its stylistic abstraction, Stephanie’s strength lies in her ability to create an intimate portrayal of emotions and vulnerabilities that are usually not overt but lurk just beneath the surface. The subtle intricacies expressed in the body language of her sculptures give us a glimpse into the fleeting and enduring experiences we have as individuals. We are reminded that although we may be surrounded by people, our experience is our own, and we carry it alone. It is heavy, but it is also very beautiful.”